Research Framework

OCCAM aims to investigate the effects of educational policy, focusing on trends and differences in educational achievement, the determinants of educational outcomes, and changes in educational outcomes from an international perspective. International large-scale studies on student achievement in mathematics, reading, and science have been conducted since the late 1960s. However, in the past, the data from these studies have been used almost exclusively for cross-sectional comparisons. OCCAM goes beyond the state of art by shifting the focus from cross-sectional correlation to longitudinal trend analysis on a country level. The European Training Network (ETN) aims to apply and develop innovative methodological approaches in its studies. It explores the research opportunities presented by the newly available data but also scrutinizes the limitations of international trend comparisons.

Overview of the Research Program

Over the last few decades, educational issues have attracted attention from a range of research disciplines, because it has become clear that the quality and quantity of education affects every aspect of individual life and influences a society’s capacity for democratic, social, and economic development. In all European countries, education serves as the main entry point to later employment; it is therefore the key to reducing youth unemployment and strengthening individual and economic development. The OCCAM research program entails two categories of interrelated objectives, based on which it will train a new generation of early-stage researchers:

- The first category concerns descriptions of educational outcomes, with a focus on changes over time in different systems for different groups of students. Educational outcomes are described in terms of levels and equity, and cognitive, affective, and attitudinal aspects are covered. We use different concepts of equity to study educational inequality as poverty (students without a basic education), dispersion, and social (e.g., gender) inequalities (cf. Robeyns, 2006; van de Werfthorst & Mijs, 2010). The aim is to gain a deeper understanding of how to describe and compare international trends relating to educational outcomes.

- The second category concerns the establishment of causal relations between educational policy and outcomes. We will provide explanations for changes in outcomes and inform discussions on different educational and societal factors. Generating new knowledge will extend existing theories on educational effectiveness regarding the effects of a large set of policy-related issues. How can countries reform their educational systems to couple high performance with equity?

In order to pursue these objectives, the research program at the ETN OCCAM makes use of the international comparative studies of educational achievement around the globe. These studies are producing data at an increasing rate, which researchers can use in secondary analyses to study differences between and within countries. Recently, for example, the EC used these data to evaluate the school systems of European Union member states (cf. Isaac, da Costa, Elena, Calvo, & Albergaria-Almeida, 2015). Such data can also be used as a basis for investigating the effects of different educational and societal factors.

Over the last 20 years, great progress has been made in the methodological procedures for establishing causal inferences from observational data, and these techniques, in combination with the vast amount of data that has been amassed in international (trend) studies, make it possible to address a wide range of important and innovative issues. To understand the OCCAM research program it is worth recapitulating some of the major empirical results from the international comparisons. Examples of differences in performance between and within countries over time are (Mullis & Martin, 2007):

- In the areas of mathematics and science, for example, these studies reveal enormous differences in the mean levels of performance between many European countries and the highest performing countries, located mostly in Eastern Asia. The observed differences correspond to the effect of approximately two years of schooling.

- The differences are even more extreme within countries. Such inequalities can be observed in the dispersion of student test scores and differences between certain groups (e.g., in terms of social background). Interestingly, the degrees of inequality also differ between domains, and they change between primary and secondary schools in the respective countries.

- One example of change over time is the sharp decline in levels of achievement in Norway and Sweden after 1995. This amounts to the effect of one year of schooling. An opposite example is the rapid increase in Finland from the 1980s—when achievement was at about the same level as the other Nordic countries—to the extremely high level that the country boasts today.

- Inequalities also change over time. One example is that the reading achievement gap between natives and immigrants has halved in Austria and Germany since 2000, whereas gender differences have almost doubled. During the same period, the dispersion of student test scores decreased in Germany whereas it increased in Austria.

OCCAM aims at a better understanding of this huge variation, with a focus on educational policy at the system and school level. As a result of our engagement with international assessments, we will also develop a critical perspective on these studies. We will explore the opportunities but also misuse, misinterpretations and other limitations of using international assessment data for research on educational systems.

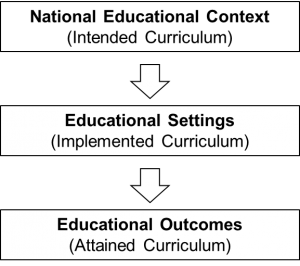

| OCCAM uses the opportunity to learn (OTL) framework as its major organizing research concept. This framework considers, first, how educational opportunities are provided for students around the world, and second, what factors influence how students use these opportunities (McDonnell, 1995). The OTL model conceptualizes curricula as functioning on three levels: (1) The intended curriculum is what national educational policies intend students to learn and how the education system is organized to facilitate this learning (e.g., including vs. segregating students with special needs). (2) The implemented curriculum relates to how the educational organizations (e.g., schools) implement such goals, what is actually taught in individual classrooms, who teaches it, and how it is taught. (3) Lastly, the attained curriculum describes what students have actually learned (e.g., scores on standardized tests) and what they think about it (e.g., interest) as well as the emergence of educational inequality (e.g., gender gaps). |  |

It is worth noting that educational systems have a multilevel structure—students are nested within classes, classes are nested within schools, and schools are nested within regions, societies, and nations. Although educational policies are typically located at higher levels, they also manifest on lower levels. In other words, educational outcomes result from complex interactions between different educational actors such as policy makers, principals, teachers, parents, and students, and different contexts such as families, classrooms, schools, and governments. For this reason, OCCAM studies direct, mediating, and moderating effects at the various levels to understand the complex mechanisms in effect between educational policies, learning processes, and outcomes (Baron & Kenny, 1986). We are especially interested in variations at the system level, because it has hardly been studied in previous research. It is increasingly possible to investigate this level of educational systems using trend data from international assessments. This approach promises groundbreaking new knowledge and a deeper understanding of the internal mechanisms of the “black box” of educational policy.

Working from the opportunity to learn/curriculum model, OCCAM uses the achievement tests from international large-scale assessments on student achievement to describe student learning in the participating countries. To form a more complete picture of these learners, schools, and systems, information from background questionnaires (for students, parents, teachers, principals) of the international studies and other relevant sources (e.g., UNESCO Institute for Statistics, World Bank) are included, providing a wealth of information.

Working Groups

The challenges of studying the effects of educational policy from an international perspective are addressed in three multilateral thematic working groups, each of which is concerned with one of the three levels of the OTL model. Each working group consists of four to seven partners cooperating closely in research and training, and combines four to six individual early-stage research projects. The first working group focuses its efforts on how to operationalize educational outcomes (attained curriculum) in international comparisons. This working group is considered a key pillar of the program as it provides the methodological foundations for the other two multilateral thematic working groups, which will concentrate on how educational policies affect the acquisition of knowledge and literacy in different contexts. Using the intended and implemented curriculum framework, these two working groups study features of the educational system within and outside school:

Working Group 1: The Integrity of Educational Outcome Measures

|

|

|

|

The first working group focuses its efforts on the attained curriculum and the educational outcomes that are actually achieved by students in international assessments. It evaluates the data quality from the original studies both conceptually and technically in order to determine the integrity of these data for use in research by the other working groups. The overall aim is to scrutinize the strengths and limitations of the current practice of comparative assessments. What can European and national policymakers learn from international comparisons of test scores in a world that is globalized but also socially and culturally diverse? How can new performance indicators that take into account prior performance and the socio-economic context contribute to policymaking?

From a technical point of view, a major concern for researchers seeking to make valid comparisons is the comparability of cognitive (i.e., achievement) measures and other constructs from background measures (i.e., motivation, social status, learning strategies) across countries and over time. One of the main criticisms of international studies is the use of multiple-choice items, because such items are not common in some countries. Thus, one PhD student investigates the measurement invariance across countries associated with item format and scoring and its influence on international comparability. A second PhD student explores issues around the cross-cultural comparability of the scales from the background surveys. The third early-stage researcher addresses the comparability of older and recent international assessments with the aim of linking them to a common metric by means of item response theory models.

Another strand of research focuses on how to draw valid inferences from the outcome measures in international comparisons. One research project investigates conceptual differences between outcome measures in different domains, grades, and years, and will investigate their relationships empirically. A further topic addressed within this working group is how to approach educational inequality in international comparisons (e.g., social inequality, gender gaps, educational poverty). We argue that educational programs and reforms should be studied in terms of efficiency and equity. Theories of justice, such as the capability approach, and theories of human rights are taken into consideration to compare different operationalizations and measures of educational equity and inequality. The last project in this WG investigates the robustness of comparing the test scores across countries, with a particular focus on the impact potential measurement error in the background variables has upon the results.

The sub-topics investigating the validity of comparisons and inferences (read more on the PhD projects):

- The influence of item format and scoring on score comparability

- Does one size fit all? Evaluating the cross-cultural validity of constructs

- Linking recent and older IEA studies on mathematics and science

- The integrity of test scores for national monitoring and comparative research

- Measuring educational inequality: competing normative foundations

- The impact of measurement error in background data on PISA scale scores

Working Group 2: Governance of Human and Financial Resources and Decision Making

|

|

|

|

|

This working group focuses on the intended curriculum, i.e., how countries organize educational systems to facilitate learning opportunities. Countries have to make choices about the implementation of funding schemes, teacher workforce policies, and the allocation of decision-making power to several stakeholders. The early-stage reseachers investigate the different patterns of decentralization, resource allocation, accountability, and competition to understand the conditions under which certain reforms do (or do not) work. The early-career researchers categorize and contrast different reforms and policies, and focus on the consequences for learning. The research contributes empirical evidence on whether the high expectations of proponents (excellence) or concerns of opponents (segregation) actually manifest in educational outcomes (levels and equity).

Market-based reforms in education are one of the most conspicuous features of the current economic and political discourse. A first hypothesis addressed in this working group is that the implementation of accountability mechanisms in educational systems can boost system-wide performance and reduce inequality. A second PhD student focuses on the interplay between performance management and school autonomy, and the effects of these reforms on educational achievement and equality, including differential effects for different students and countries. A third study concerns failing schools in decentralized school systems. Can needs-based funding mechanisms (“educational priority policies”) effectively compensate for the special demands of schools that operate in disadvantaged communities? The last two studies in this working group proceed from the notion that the quality of what happens within classrooms is limited by the quality of the teachers. The fourth early-stage researcher focuses on the consequences of how education systems select, prepare, and support a high-quality teaching force. Finally, the fifth PhD student investigates variations across countries in how teachers are distributed to schools as a function of school segregation and market mechanisms, and examines how these affect equity in schooling. Several shortcomings of previous studies with regard to causal inferences are addressed.

The sub-topics exploring the conditions under which reforms work (read more on the PhD projects):

- Reforms of teacher professionalization/accountability

- Quality at the cost of equity? Performance management, school autonomy, and instructional quality

- Effectiveness of educational priority policies

- Consequences of different teacher workforce policies

- Teaching quality and school segregation: perpetuating inequalities

Working Group 3: Educational Settings and Processes

|

|

|

|

This working group investigates the implemented curriculum, i.e., the path from policy to practice, focusing on class- and school-level features of the educational system. These are important levels for studies on educational policy because the effects of educational policies may be mediated by class- and school-level features. Moreover, different policies may moderate the relationship between class- or school-level variables and student outcomes (including levels and equity). Finally, when the primary interest lies at the class- and school-level, the use of international data has its merits: The key factors of educational settings and learning processes are typically standardized within countries but they are more diverse across countries (e.g., teachers are standardized through national teacher education programs). From an analytical viewpoint, using such international variation generally implies increased statistical power when determining the impact of specific factors on student outcomes.

Principals may be engaged in leadership duties such as budgeting, facility management, or decision making regarding instructional issues to various degrees. The responsibilities and tasks of principals vary between countries with centralized and decentralized school systems. One project investigates the impact of transformational versus instructional leadership on student achievement. Another topic is generic (e.g., achievement orientation, structuring) and content-specific instructional knowledge (e.g., the use of representations in mathematics): National curricula for qualified teachers differ in terms of how and to what extent they stress different types of instructional knowledge. To provide a more comprehensive picture of children’s learning opportunities, one early-stage researcher focuses on parental engagement in home literacy activities. This project promises particular insights into the generation of social inequalities in educational outcomes with a focus on children from workless backgrounds. Finally, previous studies that rely solely on within-country variation suggest that proximal causes of learning factors (e.g., quality of teaching, school climate) are more important than distal causes (e.g., teacher qualifications or school resources). It is important to use international data to test whether the findings from previous studies are due to the lack of variation within countries.

The sub-topics investigating the path from policy to practice within schools (read more on the PhD projects):

- Transformational and instructional leadership as levers of learning

- The impact of generic and content-specific teaching practices

- Children from workless backgrounds and the mediating role of parents

- Distal and proximal causes of student achievement

OCCAM Database

The research program of the ETN OCCAM makes use of international comparative studies of educational achievement around the globe to perform secondary analyses (cf. Hanushek & Woessmann, 2011). We consider student achievement as well as affective measures like academic self-concept, interest, and motivation. The affective measures are also potential mediator and moderator variables that influence achievement.

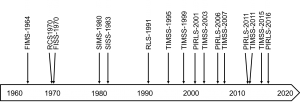

A unique contribution of the OCCAM action to the research community is the OCCAM database. The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) has conducted some of the most important international student assessments in the world. The IEA was founded in 1958 and started to develop these studies with differing target populations and an increasing number of participating educational systems. Their most popular and largest recent studies are TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study; since 1995) and PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study; since 2001). These studies assess children in primary, secondary, and upper secondary school in a four to five-year-cycle. They capture mathematics, science, and reading literacy, as well as information on student, home, school, and societal factors. These recent trend studies cover periods going back roughly 15–20 years. However, some important educational reforms, e.g., new public management reforms, were implemented before these studies were launched. For this purpose, OCCAM aims to link recent and older IEA studies by means of rigorous item response models (cf. Kolen & Brennan, 2004) in order to track long-term trends over a period of more than 40 years.

Overview of all previous IEA studies on mathematics, reading, and science that will be incorporated into the OCCAM database:

[FIMS = First International Mathematics Study; FISS = First International Science Study; PIRLS = Progress in International Reading Literacy Study; RCS = Reading Comprehension Study; RLS = Reading Literacy Study; SIMS = Second International Mathematics Study; SISS = Second International Science Study; TIMSS = Third International Mathematics and Science Study (since 1999, Trends in International Mathemathics and Science Study)]

This unique database is one of the outputs of work package 1 and will provide unprecedented opportunities to look at questions that could not be addressed in previous research.

Apart from this OCCAM database, the PhD students make extensive use of other data sources. In 2000, the OECD first launched its popular Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which covers mathematics, science, and reading attainment in 15-year-olds. While the IEA studies focus on curriculum-based knowledge and skills, the OECD studies also try to capture competencies that are important in adult life. Such conceptual differences point to distinct ideas about the role of education which will be scrutinized (e.g., OECD’s focus on the instrumental/economic role of education). Foreign language learning is one aspect that is not well represented in the IEA and OECD studies. Therefore, the EC’s European Survey on Language Competences (ESLC) was launched in 2011 in 16 European countries and educational entities; this serves as a further data source for OCCAM. Further, whenever possible the database will be extended to cover linkages with national studies. Among other data, the linkage with national studies provides prior achievement measures that address the limitations of the cross-sectional design.

Research Methods

During the last two decades, there have been methodological developments that have made it possible to address issues that were previously impossible to study.

In the fields of educational and psychological measurement, remarkable and powerful statistical methods have emerged due to the evolution of modern test theory or item response theory (IRT) and its implementation in computer software (cf. De Boeck & Wilson, 2004). The power of IRT comes from the fact that the parameters of probabilistic models of performance on test items are invariant over samples of persons and items, while the statistics computed within the framework of classical test theory are dependent on the sample of persons and the particular combinations of items used. Since the early 1990s, IRT has been used in international studies, and the use of these techniques has improved the quality of the studies immensely. IRT methodology makes it possible to implement matrix-sampling models, in which different persons take different subsets of items, as well as methods for equating the scales of different studies. The development of structural equation models (SEM) is another significant contribution to the field of measurement (cf. Muthén, 2002). By formulating models in terms of both latent and manifest variables, SEM can deal with measurement errors in observed variables. Such models can also estimate both the direct and indirect effects of chains of variables. Over the last 20 years, scholars have developed SEM in several different ways, making it suitable for use with categorical data and allowing it to address the nested structure of units of educational systems—i.e., the clustering of students in classrooms, of classrooms in schools, of schools in municipalities, and so on.

Another important strand of development concerns analytical approaches that allow valid causal inferences based on observational data (cf. Schlotter, Schwerdt, & Woessmann, 2011). The randomized experiment is a prototypical way to reach valid conclusions about causal effects, but the challenge is greater when the researcher cannot manipulate conditions in experimental designs. Indeed, many interesting research issues within the field of educational policy are not suitable for experimentation—for ethical, practical, and economic reasons. This forces researchers to rely on different types of observational data. Furthermore, it is not clear that mechanisms and effects captured in randomized experiments can be replicated more broadly beyond their local context. International assessment data contribute evidence from a variety of contexts, educational systems, and countries. However, a problem with using such data is that any associations that emerge cannot easily be interpreted in causal terms because of endogeneity. Common problems include, for example, reverse causality, selection mechanisms, or omitted variable bias. A further problem when interpreting results in terms of causality is the threat of measurement errors in observed variables. Such errors tend to result in the systematic underestimation of relations between variables. Several approaches have been developed to guard against the different threats to valid causal inference in analyses of observational data:

- One class of approaches relies on conditioning techniques. The basic strategy is to find a set of observed control variables that can be included in regression equations. Multilevel models, SEM, and propensity score matching add additional power. However, these techniques cannot remove bias due to unobserved confounders, thus conditioning is not an infallible approach for developing valid causal inferences.

- Another approach is instrumental variables regression. The idea is to find a variable (an “instrument”) that is related to an independent, endogenous variable X, but not to the dependent variable Y, apart from by the indirect effect via X. This approach is often used to deal with problems of reverse causality and errors of measurement.

- Within the social sciences, longitudinal designs are frequently used. When the units studied have characteristics that remain constant over time, the units can be used as their own controls, which brings the advantage that fixed characteristics can be omitted without causing any bias. Regression analysis with change scores or regression with “fixed effects” can be used to conduct such analyses. This approach can be applied at different levels of observation.

- The repeated cross-sectional designs that are used in the international studies have a longitudinal component at the country level. The analysis of such aggregated trend data is often referred to as “differences-in-differences analysis” and takes advantage of the strength of longitudinal designs in combination with a better handling of selection mechanisms and measurement error.

One of the main points of criticism of international studies is that the varying characteristics of nations in terms of culture, history, and populations make it impossible to draw any inferences concerning the causal effects of different aspects of the educational system. This criticism points to the problems caused by omitted variables in between-country comparisons, and justifiably so. However, most of these problems can be avoided with a country-level longitudinal analysis, as such an approach makes it possible to investigate change and development.

This description of advances in methodology for making causal inferences from observational data suggests that there are indeed tools available that can be fruitfully applied to investigate substantive research problems within the field of education. It is clear, however, that used alone each of the different methods relies on strong assumptions and have their limitations, which makes it necessary to use multiple approaches, to address possible sources of bias, and to find innovative ways to analyze the complex data from international comparative studies. Therefore, a central aim is to equip each early-stage researcher with a flexible analytical mindset, allowing them to scrutinize educational and political questions and evaluate the possibilities and flaws of the various research approaches and methods.